Publication: "Achieving Digital Wellbeing Through Digital Self-Control Tools: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis"

The last few years have seen the flourishing of Digital Self-Control Tools (DSCTs) both in academia and as off-the-shelf products. These tools allow users to self-regulate their technology use. The two screenshots, for example, are taken from Apple Screen Time, an app available on every iOS smartphone. It allows users to monitor time spent and smartphone pickups, with the possibility of defining interventions like usage timers and lock-out mechanisms for specific applications.

While these emerging technologies for behavior change hold great promise to support people’s digital wellbeing, we still have a limited understanding of their real effectiveness, as well as of how to best design and evaluate them.

To close these gaps, we conducted a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis of current work on tools for digital self-control. Our analysis was published on the ACM Trasactions on Computer-Human Interaction, and surfaced motivations, strategies, design choices, and challenges that characterize the design, development, and evaluation of DSCTs.

Overall, we found several gaps in the design and implementation of contemporary DSCTs that may inform future works in this field:

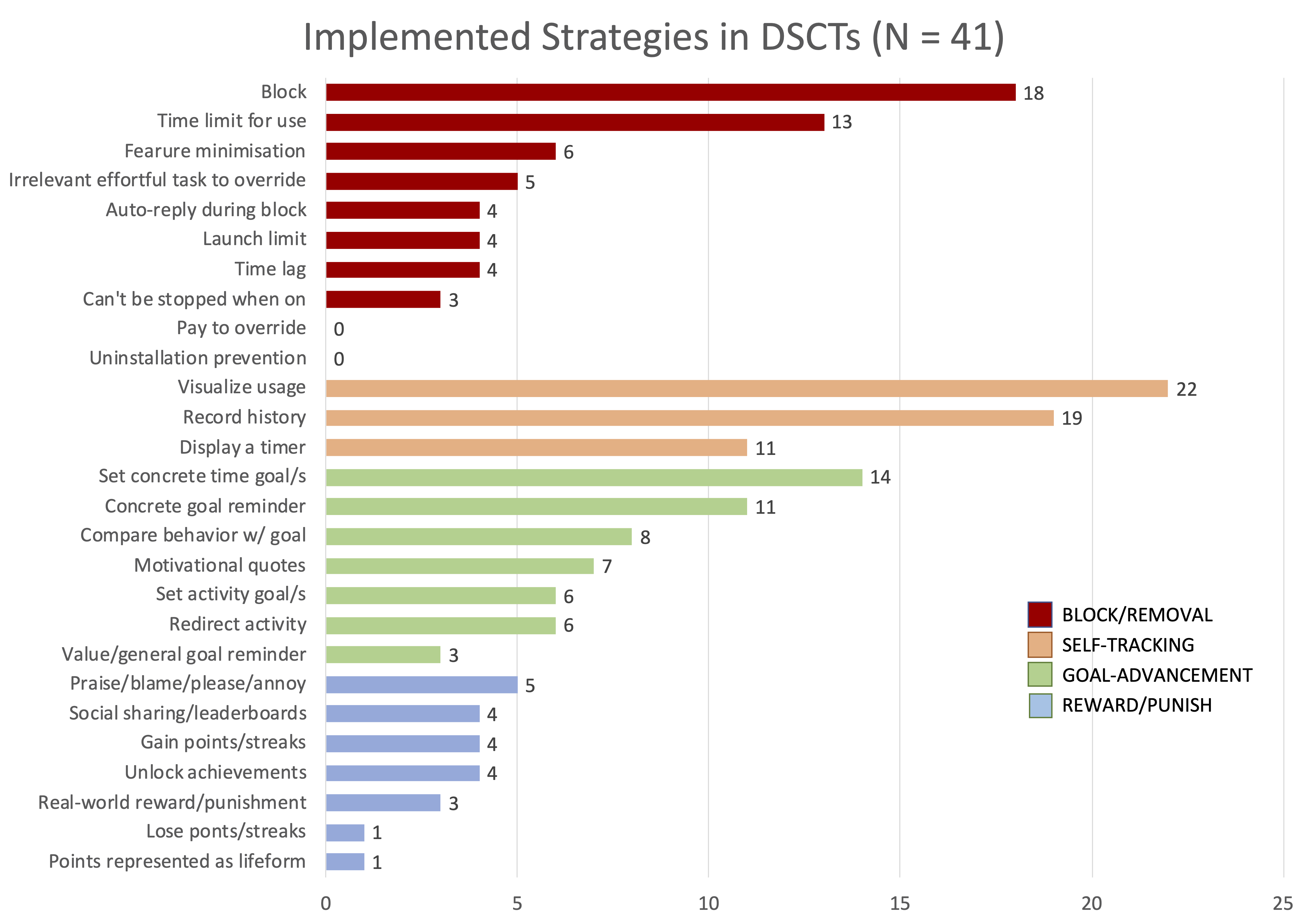

- Self-monitoring nature: as shown in the chart below, contemporary DSCTs focus on block/removal strategies (e.g., timers and lock-out mechanisms), and provide users with self-tracking tools (e.g., productivity dashboards). This means that, through DSCTs, people need to figure out for themselves the causes of their problems and possible (restrictive) solutions, which is often challenging.

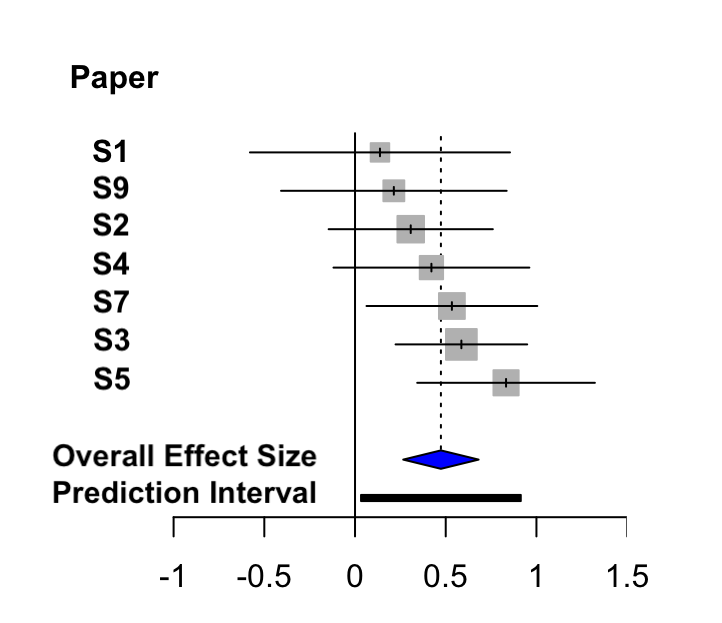

- Short-term effectiveness: contemporary DSCTs may have a short-term impact on reducing the time users spend on their devices. The chart below is extracted from our meta-analysis, and highlight such a significat effect size in 7 of the analyzed papers.

Unfortunately, our analysis also demonstrated that DSCTs are not effective in the long term, as they do not promote the formation of new habits.

-

Focus on (single-device) screen-time: contemporary DSCTs mainly focus on reducing screen time, only. Using time spent as the sole measure of people’s digital wellbeing may not be the right choice. Indeed, measures like screen time are too coarse and do not reflect the variety of goals and different kinds of tech usage of the users. Furthermore, providing users with an indication of their screen time, e.g., for self-regulation purposes, may produce negative reactions, thus inducing users to stop using the DSCT. In parallel, the majority of contemporary DSCTs only take into account the device on which they are installed, but users' digital habits are more complex: we own many devices, each with its own characteristic, and we often use more than one device at the same time.

-

Theoretical gap: DSCTs and the digital wellbeing research area are not sufficiently grounded in HCI and behavioral theories. Grounding the design of behavior change technologies on well established behavioral theories, e.g., the dual-system theory, is fundamental to generate long-lasting results.

Besides gaps in design and implementation, our analysis also revealed gaps related to how researchers evaluate their DSCTs:

- Experiments are typically short (e.g., 21 days) and cannot assess the long-term effects of using a DSCT.

- Experiments rarely include a control group, with a prevalence of within-subject experiments.

- Experiments rarely include a withdrawal phase, i.e., a phase during which the DSCT is (progressively) removed.

- Experiments have a strong selection bias towards young university students, and, more generally, towards technology-savvy users that use devices like PCs and laptops every day, e.g., for studying or working.

As we consider digital self-control tools as a great opportunity to realign technology with people's digital wellbeing, our work highlights the possibility of moving towards more ethical, theoretically-grounded tools. At the same time, we stress the need to find ways to deal with the current business model of contemporary tech companies, which nowadays incentivizes frequent and continuous usage.

Additional information: